A teaser at the top of today’s NYT Business Day, under the heading of Advertising, says: “Embedded Breaks. PBS’s ‘Nature’ and ‘Nova’ will start showing promotions in the middle of programs.”

Now I note this here on LaMarotte not in order to have a phony eruption of righteous indignation but merely to record the fact that PBS, in its very slow crossing of the Rubicon, evidently wishes to pause, mid-river, to take a brief embedded break. The fact is that our only public medium has been running advertisements for quite a long time already, enough so that exercising the mute button on that channel is also quite habitual—but, thus far, only while waiting for a program to start—or the next one to begin.

Ads, promotions, and Thank You Notes to generous foundations flanking shows, plus weeks on end of Public Begging Seminars, will now be joined by Embedded Breaks in midst of two programs only (for starters) is a little shiverish and saddening, but one gets used to it. The feeling is something akin to seeing Grandma in miniskirts, her once severe grey hair suddenly raised to a tower and dyed bright orange, her fading lips thickly over-painted by a lurid lipstick. One would like to drape her in a blanket, quickly, and put her in the van where the sunglare-glass is dark enough to hide her aging charms. Ambiguous emotions in which long respect, love, and a family feeling will not go away, where Grandma will remain forever Grandma, but please. Isn’t it perhaps high time simply to retire, to vanish from view? Honorably while honor is still possible? And we’ll pay for the tall fence to hide your degeneration from the prurient public eye.

Pages

▼

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Monday, May 30, 2011

Straws in the Wind

My reference is to the Legal Tender Act of 2011 (link), legislation that passed in Utah. It became effective March 25, 2011. The law makes federal gold and silver coinage legal tender in the state. The value of these coins may be based on their actual value as metal, not merely their face value. Why do I call this a straw in the wind?

When a society or a culture begins to break down in earnest, the functions performed at the highest level begin to be performed at a lower—in our case at the state and local level. I witnessed this myself as a boy in Germany immediately after World War II when the economy collapsed and the local currency entirely lost its value. An important memory of mine is a windy morning when, at an intersection, I saw a cardboard box chuck-full of Reichsmarks (Hitler’s currency) being blow down the street by the wind, and nobody bothered picking up the money. Black marketeering was illegal; barter was illegal too; you were supposed to exchange that worthless money, along with ration cards, for the few miserable goods actually available in stores. Our family lived by the black market, and I participated in it myself as ten-year-old helping my Father and Mother. We were busy—but acting in stealth.

When such breakdown begins, initially the actions are illegal. Then they are legalized. The Utah law is the action of a state of the Union. Someday the illegal Michigan Militia will emerge (or something like it) as the legal military force of a state that will have seen itself forced to take over defense. And Utah’s action comes in the context of the Legal Arizona Workers Act (LAWA) which the Supreme Court Upheld on May 26, 2011 (link). That law permits the State to prevent employers hiring illegal immigrants. For decades now that has seemed to me, anyway, the logical point of putting pressure on this system.

For years now I’ve been saying that the day will come when states like Kansas, say, will begin to impose tariffs on agricultural or mineral commodities leaving their borders—at first in the face of huge outcries, eventually with legal approval.

There is a word for this: Devolution. We’ve already seen that process in action, are seeing it now. It takes the entirely legal form of the Federal Government washing its hands of responsibilities and transferring the action to the states under the name of block grants. Once the duty has been transferred, the next step is to cut the actual funding of block grants gradually until the state either funds on its own or cuts it out. The Arizona law is a form of active devolution, grasping a responsibility the Federal Government is failing to perform. The Utah act is an instance of anticipatory devolution—making its citizens less subject to the sudden or slow devaluation of the dollar that, in Geithner-hands, will not be stopped by rigorous action.

At the cultural level I’ve discussed this subject as The Deformation, here. What grows complex must sometimes fall apart—unless it is a genuine improvement, maintained by deeper and more fundamental values and communal discipline. This law (“what goes up, must come done—unless it has reached and exceeded escape velocity”) applies to everything. In economics, in defense, in law generally—if the center fails, many lower centers will take over. And I’m seeing it happening now. Therefore “straws in the wind.”

But this also needs to be said: The Tea Party phenomenon is misunderstood. It is itself a sign of devolution. The party is seen as right-wing, etc., but it carries ideas, assertions, and demands that have, alas, the character of genuine value, like gold, values that time will not tarnish.

When a society or a culture begins to break down in earnest, the functions performed at the highest level begin to be performed at a lower—in our case at the state and local level. I witnessed this myself as a boy in Germany immediately after World War II when the economy collapsed and the local currency entirely lost its value. An important memory of mine is a windy morning when, at an intersection, I saw a cardboard box chuck-full of Reichsmarks (Hitler’s currency) being blow down the street by the wind, and nobody bothered picking up the money. Black marketeering was illegal; barter was illegal too; you were supposed to exchange that worthless money, along with ration cards, for the few miserable goods actually available in stores. Our family lived by the black market, and I participated in it myself as ten-year-old helping my Father and Mother. We were busy—but acting in stealth.

When such breakdown begins, initially the actions are illegal. Then they are legalized. The Utah law is the action of a state of the Union. Someday the illegal Michigan Militia will emerge (or something like it) as the legal military force of a state that will have seen itself forced to take over defense. And Utah’s action comes in the context of the Legal Arizona Workers Act (LAWA) which the Supreme Court Upheld on May 26, 2011 (link). That law permits the State to prevent employers hiring illegal immigrants. For decades now that has seemed to me, anyway, the logical point of putting pressure on this system.

For years now I’ve been saying that the day will come when states like Kansas, say, will begin to impose tariffs on agricultural or mineral commodities leaving their borders—at first in the face of huge outcries, eventually with legal approval.

There is a word for this: Devolution. We’ve already seen that process in action, are seeing it now. It takes the entirely legal form of the Federal Government washing its hands of responsibilities and transferring the action to the states under the name of block grants. Once the duty has been transferred, the next step is to cut the actual funding of block grants gradually until the state either funds on its own or cuts it out. The Arizona law is a form of active devolution, grasping a responsibility the Federal Government is failing to perform. The Utah act is an instance of anticipatory devolution—making its citizens less subject to the sudden or slow devaluation of the dollar that, in Geithner-hands, will not be stopped by rigorous action.

At the cultural level I’ve discussed this subject as The Deformation, here. What grows complex must sometimes fall apart—unless it is a genuine improvement, maintained by deeper and more fundamental values and communal discipline. This law (“what goes up, must come done—unless it has reached and exceeded escape velocity”) applies to everything. In economics, in defense, in law generally—if the center fails, many lower centers will take over. And I’m seeing it happening now. Therefore “straws in the wind.”

But this also needs to be said: The Tea Party phenomenon is misunderstood. It is itself a sign of devolution. The party is seen as right-wing, etc., but it carries ideas, assertions, and demands that have, alas, the character of genuine value, like gold, values that time will not tarnish.

Thursday, May 26, 2011

A New Minority

The Census Bureau today released full data on households in the United States as part of the official 2010 Census. Census results are based on a 100-percent count, weigh more heavily than projections or estimates made in intervening years—or such sources as the Current Population Survey. These data therefore have a certain added heft.

The upshot is that the trend made memorable by Robert D. Putnam in his book 2000 book, Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital, still holds and is gaining in strength. Putnam first published his view in a 1995 essay. The added attraction, in this release, is that in 2010, for the first time officially (which is what the decennial census is, the word) married couple families have now finally achieved the coveted minority status.

The data in summary: We had 116.7 million households in the United States in 2010. Of those 66.4 percent were family households, 48.4 percent were married-couple families, 18.1 percent families headed by a female (13.1%) or a male (5%), 33.6 percent were non-family households. The number that will be cited is that 48.4 percent, minority status for the traditional family category. Herewith a graphic. The 2010 data are from the Census Bureau’s American FactFinder facility; data for the other dates comes from the source cited in an earlier post here.

The chart is telling. Lines going downward indicate traditional and lines going up the modern style of life. The biggest gain in share of households is by non-family households, the overwhelming majority of which is men and women bowling alone. Other gains in share have been realized by single-parent households, more by those headed by females than males. The biggest loss is in married-couple families, declining from 70.5 to 48.4 percent of total households.

More than half of us are now alone—entirely or alone with children. It’s not surprising to hear the airwaves filled with talk of family values—a value rarely underlined in the 1950s when most of us, looking back, saw families in our past. The consequences of ever more children growing up in what the New York Times gently labeled “less traditional” arrangements this morning, covering this story, is beginning to become visible too, but that wave has not yet grown to its full size.

The upshot is that the trend made memorable by Robert D. Putnam in his book 2000 book, Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital, still holds and is gaining in strength. Putnam first published his view in a 1995 essay. The added attraction, in this release, is that in 2010, for the first time officially (which is what the decennial census is, the word) married couple families have now finally achieved the coveted minority status.

The data in summary: We had 116.7 million households in the United States in 2010. Of those 66.4 percent were family households, 48.4 percent were married-couple families, 18.1 percent families headed by a female (13.1%) or a male (5%), 33.6 percent were non-family households. The number that will be cited is that 48.4 percent, minority status for the traditional family category. Herewith a graphic. The 2010 data are from the Census Bureau’s American FactFinder facility; data for the other dates comes from the source cited in an earlier post here.

The chart is telling. Lines going downward indicate traditional and lines going up the modern style of life. The biggest gain in share of households is by non-family households, the overwhelming majority of which is men and women bowling alone. Other gains in share have been realized by single-parent households, more by those headed by females than males. The biggest loss is in married-couple families, declining from 70.5 to 48.4 percent of total households.

More than half of us are now alone—entirely or alone with children. It’s not surprising to hear the airwaves filled with talk of family values—a value rarely underlined in the 1950s when most of us, looking back, saw families in our past. The consequences of ever more children growing up in what the New York Times gently labeled “less traditional” arrangements this morning, covering this story, is beginning to become visible too, but that wave has not yet grown to its full size.

Monday, May 23, 2011

Compensated Maintenance

In an upscale neighborhood like mine, with Spring lawn-service contractors make their appearance right on schedule: trucks, vans, trailers, mowers, men, smell, and noise. And if the size of the estates did not already proclaim it, we can now be doubly certain where real wealth resides. Real wealth is always signaled by the presence of compensated maintenance. Now, of course, in most such neighborhoods, if they are large enough—and the Grosse Pointes in Michigan are several large communities—there are also plenty of areas where the homes and yards are modest (including mine). Therefore it is easy to see, on wide-ranging walks, the difference between voluntary, home-owner maintenance and the compensated kind. I hasten to say that in this area the over-whelming impression is order, indeed delight. Most yards are splendidly maintained and the gardens range from nice to impressive. People expend a lot of care and time. But the result aren’t uniform. I can tell where the elderly and lonely live. Over the years I’ve observed wonderful homes gradually go down hill as the once busy lady of the house—who used to be out visibly gardening, trimming, planting—has grown old and has withdrawn, and then the property itself gradually begins to mirror back her own decline. There are also, here and there, genuinely neglectful people who do the barest minimum to escape a visit from the township governments. Patches of indifference deface a block, here and there—and frequently immediate neighbors, almost by compensation one imagines, have yards and garden that are aggressively neat and splendid almost as if to fend off the blight next door.

Lawn-services, one imagines, can hardly wait for grass to grow in spring, leaves to fall in autumn, and snow to descent in winter. This is their livelihood, and the motivation is positive. In all other cases at least some part of the maintenance is wearisome, and the man or woman sighs deeply before finally venturing out to start that mower. Again. Too soon. At the same time those who deliver compensated maintenance are striving for efficiency. Therefore they use fossil fuels and chemicals of the most powerful kinds. At a time when dandelions are just past their peak—but show their colors even on the best of lawns, never a one to be seen on those estates that merit compensated maintenance. I passed yesterday one of these mansions where, on a tiny strip of bare ground six dandelion bunches lay utterly, and I mean drastically reduced to chemical death by some chemical more powerful than any I could possibly purchase at Meldrum’s or Allemon’s. Aggressive fertilizers and deadly-terminal poisons do their rapid work—and machines, machines everywhere, early spring to aerate the ground, then to mow, cut, blow. Noise. These islands of fumes and noise move at roughly twenty-minute intervals from place to place. And, surprise, the mostly Hispanic work-forces who dispense the chemicals and work the machines are the only humans I ever actually see anywhere on or even near most of these estates. Their inhabitants are invisible.

Lawn-services, one imagines, can hardly wait for grass to grow in spring, leaves to fall in autumn, and snow to descent in winter. This is their livelihood, and the motivation is positive. In all other cases at least some part of the maintenance is wearisome, and the man or woman sighs deeply before finally venturing out to start that mower. Again. Too soon. At the same time those who deliver compensated maintenance are striving for efficiency. Therefore they use fossil fuels and chemicals of the most powerful kinds. At a time when dandelions are just past their peak—but show their colors even on the best of lawns, never a one to be seen on those estates that merit compensated maintenance. I passed yesterday one of these mansions where, on a tiny strip of bare ground six dandelion bunches lay utterly, and I mean drastically reduced to chemical death by some chemical more powerful than any I could possibly purchase at Meldrum’s or Allemon’s. Aggressive fertilizers and deadly-terminal poisons do their rapid work—and machines, machines everywhere, early spring to aerate the ground, then to mow, cut, blow. Noise. These islands of fumes and noise move at roughly twenty-minute intervals from place to place. And, surprise, the mostly Hispanic work-forces who dispense the chemicals and work the machines are the only humans I ever actually see anywhere on or even near most of these estates. Their inhabitants are invisible.

Friday, May 20, 2011

An OFR We Can’t Refuse?

Around here new federal agencies empowered to collect statistical data are always a matter of interest, although, to be sure, I’d just as soon see them firmly in the hands of people deeply steeped in data collection and management activities, thus in agencies like the Bureau of the Census, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (DFA), Public Law No. 111-203, established an Office of Financial Research (OFR) but within the Treasury Department. The general idea behind this office is to standardize financial reporting requirements by regulation and to collect data on financial patterns in an effort, looking ahead, of preventing the kind of financial meltdown we’ve experienced in the Great Recession. The ears of statistical people everywhere, I’m sure, are up and listening hard.

Thus far the OFR is only beginning to organize itself. Its chief mission will be support the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). Projected staffing will be 60 people, and the up-and-running date now projected is September.

This much by way of taking note of something that might, ultimately become an important statistical lens on yet another aspect of the economy, but caution is indicated. This new baby is under the eyes of Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, not a person I think has the right stuff—whatever stuff you have in mind. OFR, therefore, may turn out to be invisible in the future, strictly supplying regulators and holding cards tight to the chest where public information is concerned. To give the public a genuine view into that thicket, finance, with reliable statistics? Why that’s downright dangerous!

The ears are up, the eyes are open. As for the rest, we’ll see.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (DFA), Public Law No. 111-203, established an Office of Financial Research (OFR) but within the Treasury Department. The general idea behind this office is to standardize financial reporting requirements by regulation and to collect data on financial patterns in an effort, looking ahead, of preventing the kind of financial meltdown we’ve experienced in the Great Recession. The ears of statistical people everywhere, I’m sure, are up and listening hard.

Thus far the OFR is only beginning to organize itself. Its chief mission will be support the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). Projected staffing will be 60 people, and the up-and-running date now projected is September.

This much by way of taking note of something that might, ultimately become an important statistical lens on yet another aspect of the economy, but caution is indicated. This new baby is under the eyes of Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, not a person I think has the right stuff—whatever stuff you have in mind. OFR, therefore, may turn out to be invisible in the future, strictly supplying regulators and holding cards tight to the chest where public information is concerned. To give the public a genuine view into that thicket, finance, with reliable statistics? Why that’s downright dangerous!

The ears are up, the eyes are open. As for the rest, we’ll see.

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

Sex Scandal Stats

Always willing to serve the people’s right to know—and what with scintillating sex-scandalous news stories springing up like Spring right now (although what we’ve seen hereabouts is unrelenting rain), I thought I’d do my duty and bring you the stats! I bring them to you courtesy of Wikipedia, that benefactor of mankind. I am an actual financial contributor to it, by the way. What I’ve done is to count the cases Wikipedia lists by period and bring them to you, appropriately enough, graphically.

Just look at those bars rising with time! Do we credit the media? Population growth, growth in population density (as in nothing propinqs like propinquity), is it a decline in morals or a increase in shameless self-display? We shall never know.

And this is, as the second chart shows, not a federal achievement. The state and locals are doing just fine. In effect, in 2010, the S&Ls were particularly randy, scoring a scandal victory by certainly more than a nose-length.

I’ve only modified incoming Wiki-data in two cases. In 2011 I added the single case of our IMF Chief's alleged episode, headline news today; and in that same year, for the S&L category, I’ve added, by way of a terminator, the revelations from California. My source is here, specifically two lists cited at the end of the See Also heading.

The first of these shows scandals at the federal level and by historical period. The periods are not the same length, to be sure. 1776 to 1899 is 124 years, the 2010-2011 period is less then two full years. But I’ve normalized these so that, what you see is average number of scandals per annum.

Just look at those bars rising with time! Do we credit the media? Population growth, growth in population density (as in nothing propinqs like propinquity), is it a decline in morals or a increase in shameless self-display? We shall never know.

And this is, as the second chart shows, not a federal achievement. The state and locals are doing just fine. In effect, in 2010, the S&Ls were particularly randy, scoring a scandal victory by certainly more than a nose-length.

I’ve only modified incoming Wiki-data in two cases. In 2011 I added the single case of our IMF Chief's alleged episode, headline news today; and in that same year, for the S&L category, I’ve added, by way of a terminator, the revelations from California. My source is here, specifically two lists cited at the end of the See Also heading.

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Women’s Earnings versus Men’s

One commenter on yesterday’s post said “Women can work in most fields at near wage parity with men. Some exceptions still apply.” Let’s a look at that. The facts are that women’s compensation consistently lags behind male compensation and has done so for at least the last 33 years. “Near wage parity” is a bit of an overstatement. Here is a graphic that shows median weekly income for men and women from 1979 to 2011. I am able to touch this year by using first quarter data in all years. Note that these numbers are in constant dollars, thus with inflationary factors removed.

The gap between the sexes has narrowed somewhat. In 1979 the median incomes were $157 apart, in 2011 $63. This means that female earnings were 61.5 percent in 1979 and 82.9 percent in 2011 of male earnings in the aggregated. But in this period female income increased in total by $55 (from $251 per week in 1979 to $306 in 2011—remember we’re dealing with constant dollars); in that same period male income has actually dropped, from $408 (1979) to $369 (2011). Female income grew at an annual rate of 0.62 percent, male income dropped at a rate of 0.31 percent. If the male income had matched the female income’s growth, the differential would be $191 (men over women) rather than $63, and women would then be earning 61.5 percent in 2011 (self-evidently) of what males earn, not 82.9 percent—thus the same gap would be present as already was present in 1979. The increasing parity between the sexes is therefore in good part mirage if it is achieved by men funding it with declining wages. The common good would be served if both series grew positively, but the female more rapidly than the male.

The sad truth is that increased participation of women in the workforce—while acting to raise female compensation, has also depressed the level of male income. And this makes “market sense” if not “human sense”: females represent a lower-cost competition to the male; males are therefore less assertive in claiming just wages because women are in effect a more affordable choice for the employer. Income parity, in other words, is being achieved, to the extent that it is, by depressing male earnings. It’s not exactly a win-win situation. The source data come for this graphic came from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Databases & Tools facility.

Let’s next look at how the sexes were doing recently (1Q of 2010) by sector:

This chart tells us that women consistently earn less than 75 percent of men, never mind the sector, the only exception being sales and office occupations. I’m particularly struck by the fact that female compensation stands at 74 percent in management, professional, and related occupations—an area where we consistently work with our heads and not with our hands. The source of this chart is BLS data here.

Let’s go deeper into that and look at two medical professions. Here I chart the earnings of Pharmacists and of Physicians and Surgeons for the period 2003 through 2009. These data are from the BLS Women in the Workforce: A Databook series, the last of which, for 2011, is available here.

Now the gender of a pharmacist has very little if anything to do with his or her knowledge of this profession, hence the differences are striking. In 2003 female pharmacists earned 89 percent of what their male counterparts earned. In 2009 75.5 percent. The closest convergence came in 2005, when the two median weekly earnings were just 7.1 points apart, females earning 92.9 percent of what males earned.

When we get to physicians and surgeons, the gaps are even bigger: 2003 - 59%, 2004 - 52.2%, 2005 - 60.9%, 2006 - 72%, 2007 - 59.1%, 2008 - 64.4%, 2009 - 64.2%.

Near parity? Some exceptions? No. What I see here, by and large, are the operations of market forces, thus of nature. Female earnings are growing at the cost of male earnings and due largely to competitive forces that, if they are mitigated at all, are mitigated minorly by weak regulatory interventions. Our own better, higher nature, which expresses itself in seeking justice and fairness, has yet to achieve much of a beachhead.

The gap between the sexes has narrowed somewhat. In 1979 the median incomes were $157 apart, in 2011 $63. This means that female earnings were 61.5 percent in 1979 and 82.9 percent in 2011 of male earnings in the aggregated. But in this period female income increased in total by $55 (from $251 per week in 1979 to $306 in 2011—remember we’re dealing with constant dollars); in that same period male income has actually dropped, from $408 (1979) to $369 (2011). Female income grew at an annual rate of 0.62 percent, male income dropped at a rate of 0.31 percent. If the male income had matched the female income’s growth, the differential would be $191 (men over women) rather than $63, and women would then be earning 61.5 percent in 2011 (self-evidently) of what males earn, not 82.9 percent—thus the same gap would be present as already was present in 1979. The increasing parity between the sexes is therefore in good part mirage if it is achieved by men funding it with declining wages. The common good would be served if both series grew positively, but the female more rapidly than the male.

The sad truth is that increased participation of women in the workforce—while acting to raise female compensation, has also depressed the level of male income. And this makes “market sense” if not “human sense”: females represent a lower-cost competition to the male; males are therefore less assertive in claiming just wages because women are in effect a more affordable choice for the employer. Income parity, in other words, is being achieved, to the extent that it is, by depressing male earnings. It’s not exactly a win-win situation. The source data come for this graphic came from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Databases & Tools facility.

Let’s next look at how the sexes were doing recently (1Q of 2010) by sector:

This chart tells us that women consistently earn less than 75 percent of men, never mind the sector, the only exception being sales and office occupations. I’m particularly struck by the fact that female compensation stands at 74 percent in management, professional, and related occupations—an area where we consistently work with our heads and not with our hands. The source of this chart is BLS data here.

Let’s go deeper into that and look at two medical professions. Here I chart the earnings of Pharmacists and of Physicians and Surgeons for the period 2003 through 2009. These data are from the BLS Women in the Workforce: A Databook series, the last of which, for 2011, is available here.

Now the gender of a pharmacist has very little if anything to do with his or her knowledge of this profession, hence the differences are striking. In 2003 female pharmacists earned 89 percent of what their male counterparts earned. In 2009 75.5 percent. The closest convergence came in 2005, when the two median weekly earnings were just 7.1 points apart, females earning 92.9 percent of what males earned.

When we get to physicians and surgeons, the gaps are even bigger: 2003 - 59%, 2004 - 52.2%, 2005 - 60.9%, 2006 - 72%, 2007 - 59.1%, 2008 - 64.4%, 2009 - 64.2%.

Near parity? Some exceptions? No. What I see here, by and large, are the operations of market forces, thus of nature. Female earnings are growing at the cost of male earnings and due largely to competitive forces that, if they are mitigated at all, are mitigated minorly by weak regulatory interventions. Our own better, higher nature, which expresses itself in seeking justice and fairness, has yet to achieve much of a beachhead.

Monday, May 16, 2011

Trends: Single-Parent Households with Children

Yesterday I mentioned, in passing, the growth of single-parent households. Today I thought I’d follow that up with a deep data series, thus back 50 years. I have these data from the Statistical Abstract (link, look at Table 59) but ultimately derived from the Census Bureau’s Current Population survey. To focus sharply on the crucial issues, the upbringing of children, I’ve selected for graphing data on households with children under 18 years of age in each category shown. Here is the graphic:

The faint bars show married couple households; the curves show female- and male-headed single-parent households—and the sum of these in red. In 1960 single-parent households represented 9.1 percent of all households with children—in my view already high. In 2009 that percentage stood at 29.5 percent!

The growth rates in this period? Well, all single-parent households with children grew an annual rate of 3.1 percent; female-headed households in this category grew at 2.9 percent a year, male-headed households had the quite astonishing 4.6 percent annual growth rate.

Well, what about married-couple households. These are (thank the Lord) still the most numerous, but they had virtually no growth at all, increasing at the rate of a mere 0.15 percent a year. This means that virtually all growth in households with children took place in the marginal categories—and the largest proportion of these in 2009 (80%) were headed by females—whose earning powers are well under those of men.

Disconnects—everywhere. Most people don’t see data like these so baldly displayed—or would know how to extract them out of the deep bowels of our statistics archives—but the feeling that something is wrong is certainly present and supported by personal observation and experience. It feeds the boiling rage that heats our current politics. Because all these endless disconnects are driving us mad! The local papers are full of sports triumphs or tragedies—and spiced with civic corruption, the closing schools, and teacher-layoffs. Nationally they drip with billions we spend in foreign wars—and at whim expend on saving revolutionaries in Libya. At home vast numbers of children live in poverty while we orate about family values. It’s time to clear all this debris, return to nation building here at home, and start once more looking for the unity that once made the United States a beacon.

The faint bars show married couple households; the curves show female- and male-headed single-parent households—and the sum of these in red. In 1960 single-parent households represented 9.1 percent of all households with children—in my view already high. In 2009 that percentage stood at 29.5 percent!

The growth rates in this period? Well, all single-parent households with children grew an annual rate of 3.1 percent; female-headed households in this category grew at 2.9 percent a year, male-headed households had the quite astonishing 4.6 percent annual growth rate.

Well, what about married-couple households. These are (thank the Lord) still the most numerous, but they had virtually no growth at all, increasing at the rate of a mere 0.15 percent a year. This means that virtually all growth in households with children took place in the marginal categories—and the largest proportion of these in 2009 (80%) were headed by females—whose earning powers are well under those of men.

Disconnects—everywhere. Most people don’t see data like these so baldly displayed—or would know how to extract them out of the deep bowels of our statistics archives—but the feeling that something is wrong is certainly present and supported by personal observation and experience. It feeds the boiling rage that heats our current politics. Because all these endless disconnects are driving us mad! The local papers are full of sports triumphs or tragedies—and spiced with civic corruption, the closing schools, and teacher-layoffs. Nationally they drip with billions we spend in foreign wars—and at whim expend on saving revolutionaries in Libya. At home vast numbers of children live in poverty while we orate about family values. It’s time to clear all this debris, return to nation building here at home, and start once more looking for the unity that once made the United States a beacon.

Sunday, May 15, 2011

Labor Force: More Musings

When the subject of male and female participation in the workforce arises, demographics tend to be ignored. Thus it turns out that participation in the workforce tends to be understated for women and overstated for men. What do I mean?

Females naturally outnumber men, but the workforce numbers are percentages of men or of women in the workforce calculated separately. In 2010, for instance, 61.99 million men were in the 25-54 age range, and 55.33 million were in the workforce; this produces the 89.3 percent male workforce participation. In that same year, the female population of the same age was 63.31 million, those in the workforce 47.61 million, and the rate was 75.2 percent participation. But if we ask, instead, how many men were in the workforce for every woman, the answer turns out that for every 10 men, 9 women labored alongside. Another way to put it is that 53.7 percent of the actual workforce at age 25-54 (102.9 million) was male, and 46.3 percent was female. In 1950 for ever 10 men at work only 4 women were required to make a go of things collectively.

What strikes me here is that that the natural (birth-based) proportion of males and females is 49 and 51 percent respectively. In 2010, both sexes were within 4.7 percent of their natural share, males 4.7 above, females 4.7 percent below. Very interesting datum! The bars are converging, folks!

Now it is said, nostalgically by some, that in the good-old-days (by which they must mean the 1950s) a man could make a living for his family all by himself. That’s obviously not statistically true if we believe Census and Bureau of Labor Statistics figures. But the 1950 proportions at least lean in that direction. We know well from history that some women always have had to fend for themselves, hence we have the word “spinster,” which once meant a woman who, without a husband, supported herself by spinning.

The by-gone ideal used to be never to labor for wages—but on your own land. But if laboring had to be done, it had best be done by the male, in dire circumstances by the woman, in the absolutely worst case by the children. From this I construct a hierarchy of economic degradation: self-supporting, wage-laboring, female-laboring, child-laboring. My bar graph therefore indicates the middle ground here somewhere, heading downward. But that’s industrialization, isn’t it?

It’s very striking that our economy absolutely demands—what with that 10:9 ratio—that women be out there working. A tiny handful, of course, are executive vice presidents, etc., but the great bulk actually labor rather than kicking ass.

It is a marvel and a mystery that in the name of wealth we’ve managed to work ourselves, pun intended, into a situation where females have no choice but to labor so that, in their ample free time, they can enjoy the great wealth of products and services that spell freedom from labor. And never mind that far too many can’t actually enjoy that wealth, because that little extra women used to go to work to earn has become necessity. And never mind that, now, now that they are working, men no longer cleave to them—so that the single-parent household, overwhelmingly female-headed, is one of the fastest-growing household categories. There were 10.6 million such households in 2007, growing at 2.1 percent a year since 1980, versus population growth in that same period of 1 percent. They held 28.8 percent of all households with children in 2007. Astounding. And, by the way, there is something we can all do. The traditional action is to take care of one’s own when the culture’s mindless axe descends.

Females naturally outnumber men, but the workforce numbers are percentages of men or of women in the workforce calculated separately. In 2010, for instance, 61.99 million men were in the 25-54 age range, and 55.33 million were in the workforce; this produces the 89.3 percent male workforce participation. In that same year, the female population of the same age was 63.31 million, those in the workforce 47.61 million, and the rate was 75.2 percent participation. But if we ask, instead, how many men were in the workforce for every woman, the answer turns out that for every 10 men, 9 women labored alongside. Another way to put it is that 53.7 percent of the actual workforce at age 25-54 (102.9 million) was male, and 46.3 percent was female. In 1950 for ever 10 men at work only 4 women were required to make a go of things collectively.

What strikes me here is that that the natural (birth-based) proportion of males and females is 49 and 51 percent respectively. In 2010, both sexes were within 4.7 percent of their natural share, males 4.7 above, females 4.7 percent below. Very interesting datum! The bars are converging, folks!

Now it is said, nostalgically by some, that in the good-old-days (by which they must mean the 1950s) a man could make a living for his family all by himself. That’s obviously not statistically true if we believe Census and Bureau of Labor Statistics figures. But the 1950 proportions at least lean in that direction. We know well from history that some women always have had to fend for themselves, hence we have the word “spinster,” which once meant a woman who, without a husband, supported herself by spinning.

The by-gone ideal used to be never to labor for wages—but on your own land. But if laboring had to be done, it had best be done by the male, in dire circumstances by the woman, in the absolutely worst case by the children. From this I construct a hierarchy of economic degradation: self-supporting, wage-laboring, female-laboring, child-laboring. My bar graph therefore indicates the middle ground here somewhere, heading downward. But that’s industrialization, isn’t it?

It’s very striking that our economy absolutely demands—what with that 10:9 ratio—that women be out there working. A tiny handful, of course, are executive vice presidents, etc., but the great bulk actually labor rather than kicking ass.

It is a marvel and a mystery that in the name of wealth we’ve managed to work ourselves, pun intended, into a situation where females have no choice but to labor so that, in their ample free time, they can enjoy the great wealth of products and services that spell freedom from labor. And never mind that far too many can’t actually enjoy that wealth, because that little extra women used to go to work to earn has become necessity. And never mind that, now, now that they are working, men no longer cleave to them—so that the single-parent household, overwhelmingly female-headed, is one of the fastest-growing household categories. There were 10.6 million such households in 2007, growing at 2.1 percent a year since 1980, versus population growth in that same period of 1 percent. They held 28.8 percent of all households with children in 2007. Astounding. And, by the way, there is something we can all do. The traditional action is to take care of one’s own when the culture’s mindless axe descends.

Saturday, May 14, 2011

Men, Women in the Labor Force

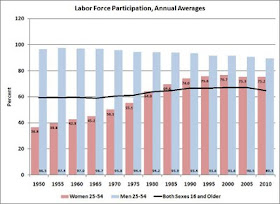

A recent column by David Brooks commenting on the decline in male participation in the labor force led me to look up the trends and the latest data on this ever-intriguing subject. Let me begin with a summary graphic from an article in the Monthly Labor Review, October 2006. It charts trends nicely from 1948 forward. The article is available here.

What it shows is that, indeed, the Bureau of Labor Statistics agrees with David Brooks. As a percent of the labor force, men are losing share of total jobs. In 1948 96.6 percent of all men aged 25 to 54 were working; in 2005 the number had declined to 90.5 percent. Corresponding figures for women were 35 percent in 1948 and 75.3 percent in 2005. Also intriguing is the fact that the elderly—55 and older—while having reached an all-time low in participation in 1995 (30%) were, in 2005, heading back up (37.2%) and almost as high as they had been in 1948 (43.3%). The chart also serves as a reminder that economic down-turns are a rather recurring pattern in our free-wheeling economy.

The next graphic updates this series using BLS data from here. I’m showing the numbers, at 5-year intervals, from 1950 to 2010. What I find striking here is that everybody’s participation has dropped thanks to the Great Recession. But while men went down 1.2 percent (from 90.5 to 89.3), women only lost 0.1 percent (going from 75.3 to 75.2). In the workforce, women are always retained longer than men. But the fault for this lies with men: they ought to insist that women be paid the same as men for all equivalent work! They aren’t. Therefore, good-bye!

These are not exactly demographic trends, which have the character of fate; but they do show broad social and economic trends worthy of a few minutes of contemplation. The contrast between 37 and 75 percent of women working outside the home (1948, 2010) surely has an effect on child-raising. The effect would seem minimal once women are into their late thirties, but earlier? In 2010 68.3 percent of women 20-24 and 74.7 percent of women 25-34 were working—ages when their children were toddlers up to teenagers. Does that affect society? The economic situation is also shown when we contemplate that 31.5 percent of both sexes aged 65-69 were still at work—and an amazingly high 18 percent of those aged 70-74! And there is also something here, though difficult to ferret out, that says something about the male’s conception of his role in society. But the less said, perhaps, the better…

What it shows is that, indeed, the Bureau of Labor Statistics agrees with David Brooks. As a percent of the labor force, men are losing share of total jobs. In 1948 96.6 percent of all men aged 25 to 54 were working; in 2005 the number had declined to 90.5 percent. Corresponding figures for women were 35 percent in 1948 and 75.3 percent in 2005. Also intriguing is the fact that the elderly—55 and older—while having reached an all-time low in participation in 1995 (30%) were, in 2005, heading back up (37.2%) and almost as high as they had been in 1948 (43.3%). The chart also serves as a reminder that economic down-turns are a rather recurring pattern in our free-wheeling economy.

The next graphic updates this series using BLS data from here. I’m showing the numbers, at 5-year intervals, from 1950 to 2010. What I find striking here is that everybody’s participation has dropped thanks to the Great Recession. But while men went down 1.2 percent (from 90.5 to 89.3), women only lost 0.1 percent (going from 75.3 to 75.2). In the workforce, women are always retained longer than men. But the fault for this lies with men: they ought to insist that women be paid the same as men for all equivalent work! They aren’t. Therefore, good-bye!

These are not exactly demographic trends, which have the character of fate; but they do show broad social and economic trends worthy of a few minutes of contemplation. The contrast between 37 and 75 percent of women working outside the home (1948, 2010) surely has an effect on child-raising. The effect would seem minimal once women are into their late thirties, but earlier? In 2010 68.3 percent of women 20-24 and 74.7 percent of women 25-34 were working—ages when their children were toddlers up to teenagers. Does that affect society? The economic situation is also shown when we contemplate that 31.5 percent of both sexes aged 65-69 were still at work—and an amazingly high 18 percent of those aged 70-74! And there is also something here, though difficult to ferret out, that says something about the male’s conception of his role in society. But the less said, perhaps, the better…

Friday, May 13, 2011

A Glimpse of Our Oil Future

The Department of Energy’s Energy Information Agency issued Annual Energy Outlook 2011. It is available here. The Outlook invites us to contemplate what things might look like in 2035 from a 2009 perspective, thus to look 27 years ahead. The report appears to emphasize natural gas—because we’re apparently doing well in that regard—even if the brightness of that future seems to be lit mostly by shale gas. I have a summary on shale on this blog, and can only agree with the EIA which also, rightly, emphasizes that there are many, many unknowns in that field.

I decided to concentrate on the petroleum liquids instead. Here in a nutshell is the EIA’s projection for that sector:

In other words, in 2009 we consumed the equivalent of 6.9 billion barrels of crude. Of that we imported 52 percent. In 2035, we shall consume just shy of 8 billion barrels of crude equivalent. Our imports will have dropped to 41 percent; some fraction of our biofuels, however, will also be imported (presumably from Brazil). The new kid on the block is liquid from coal, as high as 3 percent of our future liquid fuel. Makes me wonder where the hydrogen will come from to get that hard coal to flow.

It is difficult to discover, in such reports, “big picture” perspectives that let the reader eyeball the reasonableness of such projections. I dug out some numbers to provide myself perspective. Let’s look at petroleum reserves and consumption world-wide and in the United States.

U.S. reserves stand at 30 billion; U.S. consumption was nearly 7 billion barrels of crude equivalent. Using that number, we have 4-plus years of oil left. In effect we imported 52 percent of our oil, therefore only consumed, from domestic sources, 3.3 billion barrels equivalent. Using that number, we have nine years left.

But in EIA’s projection we have to go out 27 years and reduce our reliance on imports from 52 to 41 percent. So how is this going to happen? Well, buried in the report is the answer. The base case EIA uses includes a magic trick. The EIA magician holds out the shiny black top hat. Drum roll. And then the magician pulls 69.3 billion barrels of as yet un-discovered new reserves from the hat. These reserves will be discovered in off-shore locations all around the contiguous United States and in Alaska. Well! That’s a lot of oil! It is more than twice the reserves BP credits us as having (30 billion). Others are less generous. The Oil and Gas Journal and World Oil both think that our current reserves are just 21 billion barrels.

Other assumptions I find EIA making in building its base or reference case also strike me as rather optimistic. EIA assumes a $125 per barrel of crude price out in 2035. If I was a betting man and expected to live well beyond 99—I’ll be that age in 2035—I’d put hard cash against that number. The case also rests on other cheerful developments like a very abstemious American public, dramatically improving automotive efficiency, and an economy that will let us buy the new technology as soon as it its been delivered, presumably by Caesarean section, out of the labs.

The glasses seem tinted a shade too rosy. The curves they just keep going up. EIA is tweaking trends going downward up, with just a few token revisions. Technology wins. Foreign competition for the precious oil is muted. But that’s the nature of huge institutional establishments, like the EIA. Keep driving straight ahead, grip the wheel hard, don’t blink—but keep the pedal to the metal.

I decided to concentrate on the petroleum liquids instead. Here in a nutshell is the EIA’s projection for that sector:

In other words, in 2009 we consumed the equivalent of 6.9 billion barrels of crude. Of that we imported 52 percent. In 2035, we shall consume just shy of 8 billion barrels of crude equivalent. Our imports will have dropped to 41 percent; some fraction of our biofuels, however, will also be imported (presumably from Brazil). The new kid on the block is liquid from coal, as high as 3 percent of our future liquid fuel. Makes me wonder where the hydrogen will come from to get that hard coal to flow.

It is difficult to discover, in such reports, “big picture” perspectives that let the reader eyeball the reasonableness of such projections. I dug out some numbers to provide myself perspective. Let’s look at petroleum reserves and consumption world-wide and in the United States.

World reserves in 2009 were put at 1,239 billion barrels by BP (link) and world production, thus consumption, was 26 billion barrels the same year (link). If nothing changes—thus if no growth in consumption takes place and no new fields are discovered—we have 47 years of oil left.

U.S. reserves stand at 30 billion; U.S. consumption was nearly 7 billion barrels of crude equivalent. Using that number, we have 4-plus years of oil left. In effect we imported 52 percent of our oil, therefore only consumed, from domestic sources, 3.3 billion barrels equivalent. Using that number, we have nine years left.

But in EIA’s projection we have to go out 27 years and reduce our reliance on imports from 52 to 41 percent. So how is this going to happen? Well, buried in the report is the answer. The base case EIA uses includes a magic trick. The EIA magician holds out the shiny black top hat. Drum roll. And then the magician pulls 69.3 billion barrels of as yet un-discovered new reserves from the hat. These reserves will be discovered in off-shore locations all around the contiguous United States and in Alaska. Well! That’s a lot of oil! It is more than twice the reserves BP credits us as having (30 billion). Others are less generous. The Oil and Gas Journal and World Oil both think that our current reserves are just 21 billion barrels.

Other assumptions I find EIA making in building its base or reference case also strike me as rather optimistic. EIA assumes a $125 per barrel of crude price out in 2035. If I was a betting man and expected to live well beyond 99—I’ll be that age in 2035—I’d put hard cash against that number. The case also rests on other cheerful developments like a very abstemious American public, dramatically improving automotive efficiency, and an economy that will let us buy the new technology as soon as it its been delivered, presumably by Caesarean section, out of the labs.

The glasses seem tinted a shade too rosy. The curves they just keep going up. EIA is tweaking trends going downward up, with just a few token revisions. Technology wins. Foreign competition for the precious oil is muted. But that’s the nature of huge institutional establishments, like the EIA. Keep driving straight ahead, grip the wheel hard, don’t blink—but keep the pedal to the metal.

Monday, May 9, 2011

Hype and Reality

Since first publishing a monthly graphic (in December of 2009) based on the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ release of the employment change data, I have not shown the details underlying the single number that always makes the news. This month I’ve decided to do so. The reason for that, apart of the utility, sometimes, of seeing more details, was the current administration’s pronouncements about the April results. President Obama appeared on TV and talked about a gain of 268,000 jobs—whereas the number I reported, echoing the BLS, was 244,000. This startled me, at first—hence I went to look. Turns out that the President was concentrating on gains in private jobs and never mentioning that fact that these gains were balanced by a loss of 24,000 government jobs. They break down as follows: the federal government lost 2,000, the state governments 8,000, and local governments 14,000 jobs. These losses, needless to say, are due to failure of our elected officials to raise taxes in order to cover the services that they provide. Here is the graphic on details:

The top line, total nonfarm jobs gained, is the net of private gains and public losses. The second line is what the President was emphasizing.

Now there is no harm in emphasizing the positive, to be sure. But overstating actual gains by ignoring a sector of the economy, which suffered losses, does not raise my confidence. Rather the opposite. Aside from that, these data show some interesting trends. The big gains have come in the services providing sectors (209,000 jobs), much smaller gains in the basic sectors, the goods producing. In that category I include mining, construction, and manufacturing (a gain of 35,000 jobs). The leading gainer was retailing; it restored more jobs than our basic industries combined. When looking at the substantial gain in education and health services, we must keep in mind that virtually all actual teachers are classified as government—where job losses were shown in April. If we look at government jobs, we notice that the largest public sector occupation is elementary school teachers (as documented here). I consider them to be part of a basic industry as well.

The source data for the graphic may be found here.

The top line, total nonfarm jobs gained, is the net of private gains and public losses. The second line is what the President was emphasizing.

Now there is no harm in emphasizing the positive, to be sure. But overstating actual gains by ignoring a sector of the economy, which suffered losses, does not raise my confidence. Rather the opposite. Aside from that, these data show some interesting trends. The big gains have come in the services providing sectors (209,000 jobs), much smaller gains in the basic sectors, the goods producing. In that category I include mining, construction, and manufacturing (a gain of 35,000 jobs). The leading gainer was retailing; it restored more jobs than our basic industries combined. When looking at the substantial gain in education and health services, we must keep in mind that virtually all actual teachers are classified as government—where job losses were shown in April. If we look at government jobs, we notice that the largest public sector occupation is elementary school teachers (as documented here). I consider them to be part of a basic industry as well.

The source data for the graphic may be found here.

Friday, May 6, 2011

Employment: Update April 2011

Gradually we have become habituated to the sluggish nature of this recovery, hence, my guess, no one expected much for April and the Bureau of Labor Statistics delivered—not much in the way of good news. Employment in April went up 244,000, but fell short of the March advance which, modified this month, had been 262,000. In the 2008-2009 period we lost a total of 8.66 million jobs. Since January 1, 2010, we have recovered 1.7 million of that loss, or 19.7 percent. Gains, of course, are better than losses, but the mood, folks, isn’t right yet. Still not. Herewith the updated graphics—first the month-to-month changes and then the pie chart. The pie chart shows, as a circle, the jobs lost and the slice shows the jobs regained. Last month the slice was 16.9 percent. If the monthly gain we’ve just experienced (2.8%) holds in the future, we can expect to have recovered all of the jobs lost in 2008-2009 by May 2014.

The data shown are from the BLS press release found here.

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Two-In Front Trike

Four bucks a gallon gas does concentrate the mind—the more so when the trend line points straight up. Brigitte and I have reached the age when we remember being sixty with nostalgia. The conversation yesterday thus turned to trikes. Brigitte has long contemplated an adult version of the tricycle as something she might like to try, but her preference is for the kind with two wheels up in the front. Wheeled cycles suggests the other kind, cycles of time. When she had reached this stage in her life, my mother acquired a trike for herself, but she didn’t like it much. Such vehicles have a counter-intuitive kind of feel; you tend to lean the wrong way as you turn and suddenly stop! alarmed! because it seems like something’s wrong. I have memories of that same phenomenon myself from times when, working for Polaris, we were testing three-wheelers, the motorized kind; we later went for a four-wheeler instead. Two wheels in the front, even if you have only three all told, produce a different feel. The question then arose, as we were musing. Is there product out there for those who want the future now?

A quick and entirely unscientific survey produced three contenders: Worksman, Zigo, and Feetz. Not household names? Perhaps not. But Worksman has been around since 1898—once more suggesting that what goes around comes around. Zigo is the new kid on the block. And Feetz (whose product most appeals to us) is a Dutch company with a website available only in Dutch (here) and, so far as I can see, no visible representation in the United States.

The Zigo appears to be designed specifically to let you transport a child. The company’s spiffy website is a little bit too mobile, as it were. The images keep disappearing before you’ve had a good look at them, and the kind of technical presentations the prospective buyer longs for—seeing how the front-end carrier might be adjusted or enhanced or replaced with a different kind of accessory—can’t be found. This is a problem when, for us, the nearest dealer happens to be on Mackinac Island, thus a day’s driving away (at $4/gallon, a bit daunting).

The Zigo is priced at $1,399. Feetz is the price leader. The trike runs €1,498, but boy! does that product have features. When you turn left or right, the front wheels actually incline in the turn direction, thus this (/ /) way and (\ \) that. The mouth waters. But let’s now look at the oldest domestic product, Worksman. This company has been making industrial tricycles since the nineteenth century. Still around. It offers the right kind of bike for about $818 or thereabouts—or a four-wheeler for $1,199. Worksman, like Feetz, shows various carrier options, but the technology does not look quite as up-to-date.

The Zigo is priced at $1,399. Feetz is the price leader. The trike runs €1,498, but boy! does that product have features. When you turn left or right, the front wheels actually incline in the turn direction, thus this (/ /) way and (\ \) that. The mouth waters. But let’s now look at the oldest domestic product, Worksman. This company has been making industrial tricycles since the nineteenth century. Still around. It offers the right kind of bike for about $818 or thereabouts—or a four-wheeler for $1,199. Worksman, like Feetz, shows various carrier options, but the technology does not look quite as up-to-date.

Well, we have our work cut out for us. But that a trike is in our future seems pretty obvious. The curves point that way, don’t they? And most of our day-to-day shopping mileage is to drug- and grocery stories anyway. The economics? Tough decision. How long do we have ride a tricycle for shopping to save enough on gas to justfy the expenditures of $1,400 or thereabouts. If we want to save $20 per fill-up, and filling up every week, 70 weeks will do it, thus roughly a year-and-a-half. If we only fill up once a month because we no longer use the car as often, the pay-out comes about six years out. Ah, numbers, numbers, numbers...

Pictures, top to bottom: Feetz product, ridden and pushed. The Worksman corporate logo. The Zigo machine with baby hood. The Worksman trike. The Feetz machines with two kinds of alternative carriers. Do not be confused by "Sandd"; that is a Feetz trike. And last, not least, the Worksman trike with its simplest platform carrier.

A quick and entirely unscientific survey produced three contenders: Worksman, Zigo, and Feetz. Not household names? Perhaps not. But Worksman has been around since 1898—once more suggesting that what goes around comes around. Zigo is the new kid on the block. And Feetz (whose product most appeals to us) is a Dutch company with a website available only in Dutch (here) and, so far as I can see, no visible representation in the United States.

The Zigo appears to be designed specifically to let you transport a child. The company’s spiffy website is a little bit too mobile, as it were. The images keep disappearing before you’ve had a good look at them, and the kind of technical presentations the prospective buyer longs for—seeing how the front-end carrier might be adjusted or enhanced or replaced with a different kind of accessory—can’t be found. This is a problem when, for us, the nearest dealer happens to be on Mackinac Island, thus a day’s driving away (at $4/gallon, a bit daunting).

The Zigo is priced at $1,399. Feetz is the price leader. The trike runs €1,498, but boy! does that product have features. When you turn left or right, the front wheels actually incline in the turn direction, thus this (/ /) way and (\ \) that. The mouth waters. But let’s now look at the oldest domestic product, Worksman. This company has been making industrial tricycles since the nineteenth century. Still around. It offers the right kind of bike for about $818 or thereabouts—or a four-wheeler for $1,199. Worksman, like Feetz, shows various carrier options, but the technology does not look quite as up-to-date.

The Zigo is priced at $1,399. Feetz is the price leader. The trike runs €1,498, but boy! does that product have features. When you turn left or right, the front wheels actually incline in the turn direction, thus this (/ /) way and (\ \) that. The mouth waters. But let’s now look at the oldest domestic product, Worksman. This company has been making industrial tricycles since the nineteenth century. Still around. It offers the right kind of bike for about $818 or thereabouts—or a four-wheeler for $1,199. Worksman, like Feetz, shows various carrier options, but the technology does not look quite as up-to-date.Well, we have our work cut out for us. But that a trike is in our future seems pretty obvious. The curves point that way, don’t they? And most of our day-to-day shopping mileage is to drug- and grocery stories anyway. The economics? Tough decision. How long do we have ride a tricycle for shopping to save enough on gas to justfy the expenditures of $1,400 or thereabouts. If we want to save $20 per fill-up, and filling up every week, 70 weeks will do it, thus roughly a year-and-a-half. If we only fill up once a month because we no longer use the car as often, the pay-out comes about six years out. Ah, numbers, numbers, numbers...

Pictures, top to bottom: Feetz product, ridden and pushed. The Worksman corporate logo. The Zigo machine with baby hood. The Worksman trike. The Feetz machines with two kinds of alternative carriers. Do not be confused by "Sandd"; that is a Feetz trike. And last, not least, the Worksman trike with its simplest platform carrier.

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Rocky Mountain Low

It’s Colorado rocky mountain lowI had the unique experience the other day of filling up our car and paying more than $4 per gallon. The bill bravely approached but then kindly stayed just this side of $50. Not for long, I would suppose. Herewith the latest on gas prices across the country, as of May 2, 2011, courtesy of the Energy Information Administration here.

It’s rainin’ fire elsewhere but here prices are below

Friends around the campfire and everybody’s high

Why? Rocky mountain low!

With apologies to John Denver

Data are by regions. Sub-regions are shaded light and the U.S. average red. I live in the Midwest, and the price shown there, $4.01, is on the optimistic side. It was higher in actuality where I bought my gas. The West Coast can legitimately mourn, especially California, but this time, anyway, Rocky Mountain Low!

I’m also showing, next and from the same source, price tends for the United States from end of October 2008 through the end of April of this year. Somehow I seemed to have missed that dip in December of 2008, but, as the young now say, whatever…

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

Age Demographics - Ouch!

Interesting data on Market Size Blog yesterday on work force projections made me wonder about underlying demographic trends. With that in mind I’ve made two graphics to show how the Bureau of the Census is projecting population out to 2020 by age groups (link). The Census goes much farther out, but 2020 is, as it were, well beyond my age horizon, so I stopped there.

This shows you actual population projections by narrow age groups. While most employment-related data are gauged to 16-and-older, for projection purposes the Census makes its break at 17. For my current purposes, therefore, I show, in bold colors, the working population as ages from 18 to 64 inclusive. The others I label as “young” to the left and “elderly and old” on the right. Notice here that significant growth is shown in the 65-and-over category.

If we look strictly at “share of population,” we discover that both the Working Age and the Young are losing share out to 2020. The only group that’s gaining share are the Elderly and Old. The biggest losses in share are experienced by those who must support the other two groups. That is shown graphically below:

Not surprisingly, therefore, the Bureau of Labor Statistic, which Market Size Blog is citing, shows an increase for the 2008-2018 period of 12.6 percent in the labor force but a 25.1 percent increase in the civilian population (link).

Ouch, you might say. My sad experience is, however, that demographics is fate. I had it easy in my working years: plenty of us, and to spare, to support the generation coming and leaving while the rest of us labored.

This shows you actual population projections by narrow age groups. While most employment-related data are gauged to 16-and-older, for projection purposes the Census makes its break at 17. For my current purposes, therefore, I show, in bold colors, the working population as ages from 18 to 64 inclusive. The others I label as “young” to the left and “elderly and old” on the right. Notice here that significant growth is shown in the 65-and-over category.

If we look strictly at “share of population,” we discover that both the Working Age and the Young are losing share out to 2020. The only group that’s gaining share are the Elderly and Old. The biggest losses in share are experienced by those who must support the other two groups. That is shown graphically below:

Not surprisingly, therefore, the Bureau of Labor Statistic, which Market Size Blog is citing, shows an increase for the 2008-2018 period of 12.6 percent in the labor force but a 25.1 percent increase in the civilian population (link).

Ouch, you might say. My sad experience is, however, that demographics is fate. I had it easy in my working years: plenty of us, and to spare, to support the generation coming and leaving while the rest of us labored.

Monday, May 2, 2011

Core Unemployment

All through my working years, I kept hearing it repeated that a certain level of unemployment was unavoidable in any free economy. It was loosely referred to as “core unemployment.” It was said to be somewhere between 4 and 4.5 percent. The technical name of this kind of unemployment is “frictional” unemployment—meaning that it takes people who lose their jobs to find new ones—and for employers who lose their employees involuntarily to replace them.

I found the following useful definition of that adjective in a Bureau of Labor Statistics paper here, attributed in a quote to Frank C. Pierson of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1980:

As always in these contexts, unemployment is nonfarm unemployment. (The reason why farm employment gets a pass is itself an interesting subject I might take up one of these days.) Data are from this BLS facility. The graphic presents an interesting picture. Short-duration unemployment is essentially flat, and asking for a trend line for this period, I found it absolutely flat. It is affected by recessions, shown in shaded areas, but not a great deal. Unemployment at longer durations, particularly the gut-grinding 15-weeks and over, are a much better indicator.

Frictional or core unemployment—thus the more or less unavoidable kind, is minimally described by the black line. In this 123-month period, it produced an average unemployment for the period of 1.9 percent. The 5-to15 category, averaged 2.6 percent, the two together 4.4 percent. Perhaps there is something to the common wisdom that “core unemployment” runs about 4.5 percent. In this same period, the longest duration (15-weeks or greater) averaged 1.7 percent unemployment. And that category, signals genuine problems: a shrinking of available jobs.

I find it amusing that Frank C. Pierson (above) described structural unemployment as employers unable to find employees in 1980—when, in the year before, unemployment averaged 5.9 percent—whereas I see structural unemployment in 2011 as employees seeking jobs that simply aren’t there—when, in the year before, I see unemployment averaging 9.6 percent.

I found the following useful definition of that adjective in a Bureau of Labor Statistics paper here, attributed in a quote to Frank C. Pierson of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1980:

Unemployment can be said to be structural in nature if aggregate demand is high enough to provide jobs at prevailing wages for everyone seeking work but job openings remain unfilled because of a persistent mismatching of skills or geographical locations. If the mismatching is resolved voluntarily through mutual search by workers and employers in a reasonably short period of time, say 8 or 10 weeks, the resulting unemployment falls in the frictional category.Frictional unemployment is not reported by BLS as such, but the agency does provide unemployment by duration. With that in mind I plotted unemployment for the period 2001 through early 2011 by categories of duration: less than 5, 5 up to 15, and 15 weeks or longer. Here is the result:

As always in these contexts, unemployment is nonfarm unemployment. (The reason why farm employment gets a pass is itself an interesting subject I might take up one of these days.) Data are from this BLS facility. The graphic presents an interesting picture. Short-duration unemployment is essentially flat, and asking for a trend line for this period, I found it absolutely flat. It is affected by recessions, shown in shaded areas, but not a great deal. Unemployment at longer durations, particularly the gut-grinding 15-weeks and over, are a much better indicator.

Frictional or core unemployment—thus the more or less unavoidable kind, is minimally described by the black line. In this 123-month period, it produced an average unemployment for the period of 1.9 percent. The 5-to15 category, averaged 2.6 percent, the two together 4.4 percent. Perhaps there is something to the common wisdom that “core unemployment” runs about 4.5 percent. In this same period, the longest duration (15-weeks or greater) averaged 1.7 percent unemployment. And that category, signals genuine problems: a shrinking of available jobs.

I find it amusing that Frank C. Pierson (above) described structural unemployment as employers unable to find employees in 1980—when, in the year before, unemployment averaged 5.9 percent—whereas I see structural unemployment in 2011 as employees seeking jobs that simply aren’t there—when, in the year before, I see unemployment averaging 9.6 percent.

Sunday, May 1, 2011

Phake Products of the Pharm

Our beef today is with strawberries and, specifically, with those distributed by Driscoll’s, formally Driscoll Strawberry Associates, Inc., of Watsonville, CA 95077—just in case you wish to send them a thumbs-down letter yourself. Their slogan is “Follow us to the Farm,” but I fear that if I followed them, I would encounter there some kind of phactory that makes phake strawberries that look great, are supernaturally big, have zero taste if you disregard a kind of sour yuk and potato-like innards, and a tendency rapidly to rot phrom within. Brigitte and I stood above a Discoll’s box of so-called strawberries—this after tasting one or two and cutting up a bunch more—and we put out our arms, balled our fists, and cursed this shoddy product of modern engineering and its phabricator (surely not grower) Driscoll! Enouf already oph this crap you put out, Discoll’s, not least your so-called blueberries, the size of tangerines, with color that doesn’t even turn the tongue blue, and a taste just like so-called strawberries. No more of our dollars will go Driscoll's way iph we can help it!

Unemployment: Long-Term Trend

I undertook the tedium of charting unemployment, by month, from January 1948 until March 2011 using data obtained from a Bureau of Labor Statistics facility here. These data, like all employment and unemployment data always, refer to nonfarm employment. I’ll show the data first then them make some comments.

Two rather interesting facts become apparent. One is that our current recession was not the most dramatic—at least not if viewed through the unemployment lens. We experienced the worst unemployment in this 63-plus-year period in November and December of 1982, spilling over into 1983. Beginning in September of 1982 and ending in June of the following year, we had a period of ten months in which unemployment exceeded 10 percent, reaching 10.8 in the peak months already noted. The lowest rates we’ve experienced in this period came in May and June of 1952, 2.6 percent in each of those months. In the 1952-1953 years, we had thirteen months in which unemployment was less than 3 percent. Our own highest, in this set of numbers, came in October 2009 (10.1%). The rate reached 10 percent only in that one month throughout the 2007-2011 period. Now some people say that many are giving up and therefore are not even counted among the unemployed—and that may be true.

The second interesting observation here is the trend, marked in red. It is based on 759 monthly data points, hence it is not a trivial calculation. The trend shows that unemployment levels have been steadily rising. Until about 1987, we could expect unemployment rates to be nearly 5 but under 6 percent. After that our expectations must be for a sustained unemployment level over 6 percent—and rising.

The economy needed more people to sustain it in the early part of this history than it now needs. What happens to the people who’re no longer needed?

Two rather interesting facts become apparent. One is that our current recession was not the most dramatic—at least not if viewed through the unemployment lens. We experienced the worst unemployment in this 63-plus-year period in November and December of 1982, spilling over into 1983. Beginning in September of 1982 and ending in June of the following year, we had a period of ten months in which unemployment exceeded 10 percent, reaching 10.8 in the peak months already noted. The lowest rates we’ve experienced in this period came in May and June of 1952, 2.6 percent in each of those months. In the 1952-1953 years, we had thirteen months in which unemployment was less than 3 percent. Our own highest, in this set of numbers, came in October 2009 (10.1%). The rate reached 10 percent only in that one month throughout the 2007-2011 period. Now some people say that many are giving up and therefore are not even counted among the unemployed—and that may be true.

The second interesting observation here is the trend, marked in red. It is based on 759 monthly data points, hence it is not a trivial calculation. The trend shows that unemployment levels have been steadily rising. Until about 1987, we could expect unemployment rates to be nearly 5 but under 6 percent. After that our expectations must be for a sustained unemployment level over 6 percent—and rising.

The economy needed more people to sustain it in the early part of this history than it now needs. What happens to the people who’re no longer needed?